The recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations across the world have inspired the formation of new, black-led anti-racist groups in Scotland such as Edinburgh in Solidarity for Black Lives Matter. Here, Henry Dee explores a previous upsurge in anti-racist organising in Edinburgh through the Lothian Black Forum, prompted by the murder of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh in 1989.

The Lothian Black Forum (LBF) rose to prominence through its 1989 campaign to recognise the murder of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh as a racist crime.[1] Sheekh was a Somalian student who had been killed by white Scottish fascists on Edinburgh’s Cowgate in January 1989. The police refused to recognise the incident as a racist attack, which led to a series of anti-racist protests. Sheekh’s murder was part of a wider rise in racist attacks across Scotland in the late 1980s. The Runnymede Trust reported that between 1988 and 1990 racist incidents doubled in the Lothian and Border region and increased by almost 300% in the Strathclyde region.[2] It was in this context that the LBF challenged Scotland’s pervasive culture of denialism about racism.

Axmed Abuukar Sheekh’s murder is part of a far longer history of racism in Scotland.[3] As highlighted by the recent Black Lives Matter campaigns in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Inverness, Scottish intellectuals, merchants, missionaries, engineers, bureaucrats and adventurers were all key agents of empire abroad. At the same time, Black and Asian immigrants and students faced regular everyday indignities closer to home in Scotland itself. The African Races Association of Glasgow dissented against racist violence and rioting in the city in 1919.[4] In 1927, members of the Edinburgh Indian Association (EIA), Edinburgh African Association and Edinburgh West Indian Association successfully challenged the introduction of “colour bars” in the capital’s restaurants and cafes.[5]

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were numerous protests against the injustices of British imperialism, and campaigns against apartheid in South Africa continued into the 1990s.[6] From the 1970s, new immigrants from South Asia and East Africa experienced “a great deal” of everyday street racism and became outspoken critics of racism closer to home.[7] Arguably, the first political organisation focused on combatting local racism was the Indian Workers’ Association, which established a branch in Glasgow in 1971. The Campaign Against Racism was subsequently founded in 1976, and following the rise of the National Front (NF), annual anti-racist demonstrations took place on Saint Andrews Day in Glasgow from 1984.[8] Scottish police continued to deny the existence of racism – but, as noted by the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism magazine, Axmed Abuukar Sheekh’s whole experience in Britain was one of racism. From the racism of the state that detained and criminalised him for being a refugee, to the racism of the youths on the streets of Edinburgh who murdered him.[9]

In contrast to established groups in the Scottish capital, such as the Edinburgh Indian Association (which by the 1980s solely focused on cultural organising) the LBF was at the forefront of a new wave of explicitly political anti-racist campaigns, responding to the increased incidence of racist attacks. Rowena Arshad, a founding member, reflected that the “LBF were a group of people who dared to challenge the situation and call it racist.”[10]

The murder of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh

After being arrested for his opposition to Somalia’s military regime, Axmed Abuukar Sheekh had come to Britain in 1987 in order to support his family. He was initially detained for three months in a prison ship in Essex, England. With his immigration status still unconfirmed, he started at Stevenson College, in west Edinburgh, which actively supported asylum seekers.[11] Sheekh hoped to study medicine or science at Edinburgh University. On 16th January 1989, however, Sheekh and a Somalian friend were attacked by a gang of eight to ten fascist “football casuals”, some of whom were connected to the National Front.[12] “Screaming racist abuse, the thugs repeatedly punched, kicked and stabbed the two black students on the head, arms and body.”[13] His friend was hospitalised. Sheekh died of stab wounds.[14]

In May 1989, Terence Reilly was charged with Sheekh’s murder. He was sentenced, however, to just 21 months for possessing a knife and assault by an all-white jury. Reilly was “a self-confessed fascist”, and in the weeks before the trial police discovered him writing racist letters in his cell. His accomplice, Francis Glancy, was acquitted after turning crown witness. The rest of the assailants were never charged, and no-one has ever been prosecuted for Sheekh’s murder.[15] After sentencing, LBF spokesperson Abdourahim Said Bakar declared:

It looks as though they have been given a free hand to go about bashing or murdering black people knowing that nothing will be done about it […] If it had been the other way round and a black person had killed a white people, some parts of the media would have gone wild. Yet this has been reported in the local paper and nowhere else. It is appalling. It is as if the death of a black person is not important.[16]

Campaign Against Racism and Fascism denounced the “strongly entrenched” belief that “Scotland was a ‘non-racist country’”, and “how hard the authorities would work to ensure that this façade remained intact.”[17] A Trotskyist newspaper, The Workers’ Hammer, likewise, rebuked the fact that the obscene spectacle of racist ‘justice’ gives the green light for fascists to carry out their murderous attacks […] the murder of Ahmed Shek and the subsequent whitewash gives lie to the myth that in Edinburgh, the so-called ‘Athens of the North’, seat of Labour administered Lothian Region and capital of ‘enlightened’ Scotland, there is ‘no racism’[.][18]

The Lothian Black Forum

The LBF was Black-organised and Black-led, drawing together activists of African and Asian descent. Its early leaders had all individually been discriminated against by an “unforgiving system” – job prospects were bad and their children faced difficulties in school.[19] Rowena Arshad was director of the Multicultural Education Centre and a member of the teacher’s union, the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS).[20] Mukami McCrum was a co-founder of Shakti Women’s Aid, a Black women’s refuge in Edinburgh which had been founded in 1985.[21] Uma Kothari was a geography PhD student at Edinburgh, and Shakti’s other co-founder. Tarlochan Gata-Aura had been a leading member of the United Black Youth League in Bradford, which campaigned against fascism, racism and the deportation of Asian workers during the early 1980s. He was one of the Bradford 12 who were arrested in July 1981 after they made petrol bombs to defend their community against the National Front.[22] LBF members also included the future journalist Gary Younge, who was studying French and Russian at Heriot-Watt University, as well as Philomena de Lima, who was a Sociology MA Hons and PhD student at the University of Edinburgh between 1975 and 1982, before moving to the Highlands where she continued to be active in highlighting racism in rural areas.[23] Initially, the LBF was based in the Multicultural Education Centre at Leith Walk Primary School, where Rowena worked.

The LBF had a “pretty high level of political sophistication” according to Younge, recognising the relationship between racism, gender and social class.[24] Above all, the LBF achieved a strong sense of cohesion and community among politically Black activists in Edinburgh, galvanising people to create their own space. It gave a grounding from which Black Scottish people could respond to racism, and it was how university students like Gary Younge got to know other Black people in Scotland. Arshad and McCrum, in a paper for the Scottish Government Yearbook journal in 1989, explicitly rejected the “numbers debate” (in reference to Scotland’s allegedly small Black population), insisting it was “immaterial if there was none, one or one hundred blacks per square mile, as the issue of equality within policies and general combatting of racism still exists.” Foregrounding the importance of intersectionality, they also emphasised how “the triple oppression of race, gender and class determine the lives of black women”, and argued that “the popular view that Scotland has ‘good race relations because there is no racism here’ has meant that not only is the position of black Scottish women ignored, it is actually worse.”

Real change would mean accepting that racism does prevent black women’s full participation on equal terms in the political, social, economic and cultural life of Scotland. Instead of taking back women as objects of research or groups in ’need’, it is more advisable for politicians and policymakers to uncover class and gender specific mechanisms of racism amongst white society.[25]

Throughout 1989, the LBF held public meetings, with hundreds of Edinburgh residents in attendance, calling for the police to recognise the death of Axmed Sheekh as a racist murder. Racism was a pervasive issue in Edinburgh. Bin men called out racist names, young boys were assaulted going to and from school, and LBF received a lot of hate mail from right-wingers, addressed “To Mr and Mrs Black”, which included threats to disrupt the LBF’s marches and organising. When Rowena first met Gary Younge at a LBF meeting, he testified about being chased up Lothian Road by two men carrying baseball bats.[26] Many locals had insisted these men were English visitors who had come up north, rather than Scots. Younge went on to chair a committee, the Lothian Working Group on Racist Violence, which provided recommendations for the services supporting Black students in the aftermath of the Sheekh attack.[27]

The LBF also had wider support. By mid-1989, the organisation was based at the Trade Union Resource Centre on Picardy Place, and had financial assistance from trade unions, including the EIS.[28] In light of the threatening letters, the LBF were offered physical protection from fascists by the James Connolly Society, a local working-class organisation named after the famous Edinburgh-born socialist, trade unionist and Irish republican. Joan Weir, who had mentored Sheekh as part of a Scottish Refugee Council initiative, also worked with the LBF. She contacted a solicitor, and through criminal injury compensation, won money for Sheekh’s family and his friend. In June 1990, Weir printed a booklet, The Murder of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh, criticising police racism and inaction:

We believe that the murder in the streets of Edinburgh has shown beyond all reasonable doubt that a ‘racist culture’ exists in Scotland that results in black people becoming a visible target […] why do the authorities continue to down play the fact that there is organised racism in Scotland?[29]

“Scotland’s first anti-racism demonstration”

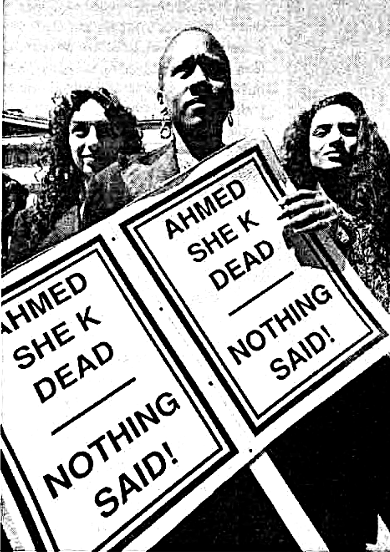

In response to the trial verdict, the LBF organised a protest march on 3rd June 1989. Before the march there was a lot of angst about safety, especially for those with kids. This was the first anti-racism march in Edinburgh, and they were uncertain about the presence of the National Front and other groups. Rowena, for example, was on the march with a pushchair. A number of single mothers wrote to LBF saying that they wanted to come, but were wary about the safety of their children. The march itself went well, ending on the Mound, next to the National Portrait Gallery, just off Princes Street. Mukami McCrum chaired the rally. The support was good, and it gave McCrum a real sense of people power. The Workers’ Hammer reported that

1500 outraged students, trade unionists, including a contingent from Stevenson College, leftists and minorities joined a militant protest – widely described as Scotland’s first anti-racism demonstration – called by the Lothian Black Forum.[30]

The event was constantly hassled by police, however. Chant leaders with megaphones were harassed, placards were confiscated, and trade unionists from the Transport and General Workers’ Union, carrying a banner with a portrait of James Connolly, were forced to the back of the march. When the LBF tried to collect money at the Mound, police insisted that they didn’t have a permit and tried to seize the donation cannisters. McCrum announced that the police had asked for people to stop collecting in the streets, but that there was no law against choosing to give money. She declared over the megaphone: “We are so noticeable when we collect money, but [they] don’t see us when we are being kicked in the streets”.[31] In defiance, donations increased.[32]

The aftermath of June 1989

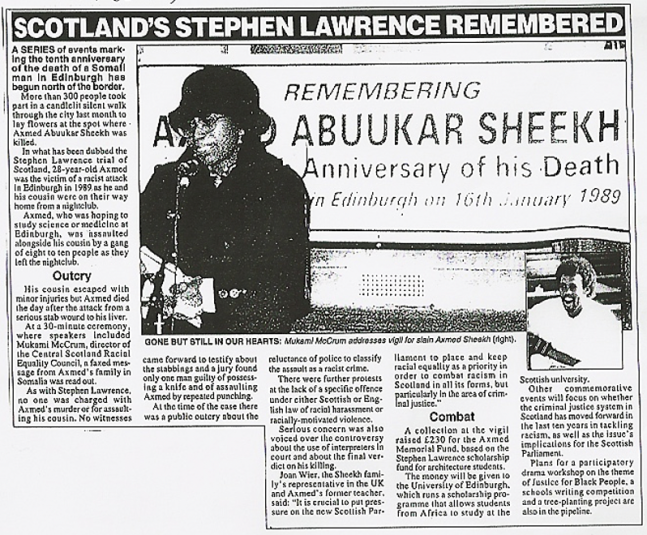

As a result of the protest, the story of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh’s murder didn’t go away. Numerous reports appeared in the Scottish and British press. McCrum insisted, “someone out there knows who murdered him. Ahmed is dead, and if Terence Reilly didn’t kill him, someone else must have.”[33] Five months after the original verdict, the police acknowledged that it was a racist murder. The idea that there was no racism in Scotland, however, was more persistent. Younge remembered newspapers continuing to talk about the idea of “catching the English disease”, or asked questions like “can racism exist in Scotland?” He described a “pathetic” piece in the Guardian’s culture section, insisting there wasn’t any racism in Scotland.[34] For many, including Edinburgh University’s Student newspaper, racism was “a relative newcomer to the political agenda north of the border” in the early 1990s.[35]

Because it didn’t have funding, the LBF itself petered away after the success of the Sheekh case. Members were exhausted, unpaid, and had families and jobs at the same time. Mukami McCrum recalled that burn out was very high, and Gary Younge remembered that the LBF constantly felt “like they had their back against the wall”. Similar issues, however, continued throughout the 1990s. After being beaten up by Glasgow police in 1991, lawyer Aamer Anwar had to campaign for four years before the incident was recognised as a racist assault. Subsequently, after Surjit Singh Chhokar was killed by three white men in Overtown, North Lanarkshire, in November 1998 – what Rowena calls “Scotland’s Stephen Lawrence case” – it took lawyers 17 years to get justice.[36] The “numbers debate” – centring on the idea that “Scotland doesn’t have a problem because we don’t have blacks” – continued, and after the collapse of a second trial of Chhokar’s murderers in 2000, Anwar declared:

We have two systems of justice at work in this country, one for whites and a very different one for black people and the poor. The Crown Office is a white gentleman’s colonial club shrouded in the vanity of wigs and gowns relatively unchanged for 400 years.[37]

Some of the LBF group, most notably Mukami McCrum, remained heavily involved in local organising work and government work. Gary Younge went on to work for a local Edinburgh youth group, which created a space for mixed-race kids to meet and young Scottish mums to discuss identity. He continued this work until the end of his degree in 1992, alongside Carl Young, another youth worker. Rowena herself went on to chair the first Black Workers’ Conference of the Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC) in 1995. This was a “monumental change”, and it was not until 2017 that the STUC had its first Black president. Today, many LBF leaders are prominent intellectuals and public figures in Scotland, and beyond.[38]

The LBF was at the forefront of a new wave of anti-racist organising in Scotland. Gary Younge recalls that there was “a strong sense of Scottish particularism” at the time. Scotland was still reeling from the poll tax. Forty-nine Scottish Labour MPs were elected in 1992, in contrast to Tory-dominated England, and it was commonly perceived that Scotland had different issues. The white-led Scottish anti-apartheid movement raised money but was focused on fighting racism in South Africa rather than Scotland. Attitudes changed through organisations such as the LBF, Supporters Campaign Against Racism in Football and the Lothian branch of the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism. Linking campaigns in Scotland with the global battle against apartheid, at Edinburgh’s 1990 May Day rally the LBF’s Mukami McCrum spoke alongside Eric Mokgathle, a leader of the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) and a visiting student at Edinburgh University.[39] On 30 November 1991, over 1,000 people attended Scotland’s annual day against racism and fascism.[40] 2,500 people, including a busload of students from Edinburgh, attended a rally in Glasgow on Sunday 29th November 1992 “to protest at the doubling in the last two years of racist attacks in Scotland and to call for more awareness of the problems faced by black and Asian students”.[41]

Conclusion

The LBF organised the first Black-led campaign in Edinburgh to explicitly challenge the denial of racism. As Priyamvada Gopal has recently reflected, the insistence that racism is only an issue in America and “not a problem here” is widespread throughout Britain.[42] It has been a particular issue, however, in Scotland. The facade of Scotland as a “non-racist country” has meant that racist assaults and murders in the late 1980s and early 1990s were not investigated by the police or brought to justice.[43] The ongoing investigation into the death of Sheku Bayoh in police custody in May 2015 is the first public inquiry to examine whether race was a factor, pointing to enduring blind-spots.[44] The blindness of a society that “doesn’t see race” meant that Axmed Abuukar Sheekh’s family were denied justice, at the same time as his fascist killers were empowered to walk free or only serve fleeting sentences.[45] Scotland should champion the aspects of its history where people-powered anti-racist organisations, like the LBF, affected change. But it should also recognise that racism has, and still does, define Scottish society. Last month, LBF leader Mukami McCrum once again highlighted these issues at a Black Lives Matter event.

[1] I’m very grateful to Rowena Arshad, Philomena de Lima, Mukami McCrum, Joan Weir and Gary Younge for sharing their memories of the LBF.

[2] J. Evans, African/Caribbeans in Scotland: A Socio-Geographical Study (PhD, University of Edinburgh, 1995), p.214.

[3] A. Dunlop, ‘A united front? Anti-racist political mobilisation in Scotland’, Scottish Affairs, 3 (1993); N. Davidson, M. Liinpaa, M. McBride & S. Virdee, No Problem Here: Understanding Racism in Scotland (Edinburgh, 2018).

[4] J. Jenkinson, ‘Black Sailors on Red Clydeside: Rioting, Reactionary Trade Unionism and Conflicting Notions of Britishness Following the First World War’, Twentieth Century British History, 19:1 (2008).

[5] H. Dee, ‘Uncovering Edinburgh: Rethinking Race and Empire in Scotland’, Republic, 3:1 (2019) https://republic.com.ng/vol3-no1/uncovering-edinburgh/ (accessed 03/06/2020).

[6] G.A. Ross, European Support for and Opposition to Closer Union of the Rhodesias and Nyasaland, with Special Reference to the Period from 1945-1953 (M. Litt, University of Edinburgh, 1988), pp.310-312. The SCRAN holds a rich collection of photos. See, for example, ‘African students demonstrate about inequality in Rhodesia, at the Mound, Edinburgh’ https://www.scran.ac.uk/database/record.php?usi=000-000-531-630-C&scache=4y7mtgmk1l&searchdb=scran, and ‘Anti-Apartheid demo 1983’ https://www.scran.ac.uk/database/record.php?usi=000-000-585-378-C&scache=5ya3egmk13&searchdb=scran (accessed 03/06/2020).

[7] Correspondence with Philomena de Lima, 15/06/2020. Indian shopkeepers in Leith, in particular, were targeted with physical and verbal abuse.

[8] A. Dunlop, ‘A United Front?’, pp.94-95; 99.

[9] ‘Remember Ahmed’, Campaign Against Racism and Fascism (February/March 1992), http://s3-eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/wpmedia.outlandish.com/irr/2017/05/25115344/no.6.pdf (accessed 03/06/2020).

[10] Interview with R. Arshad, 17/01/2020. Rowena Arshad noted that there are more files relating to the LBF’s history stored at Moray House, Edinburgh.

[11] Interview with J. Weir, 07/07/2020.

[12] J. Weir, The Murder of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh: Questions from the Abuukar Sheekh family and Somali Friends (Edinburgh, 1990). I’m grateful to Joan Weir for sharing a copy of this with me.

[13] ‘Racist Murder in Edinburgh’, Workers’ Hammer (July/August 1989), https://marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/workershammer-uk/108_1989_07-08_workers-hammer.pdf (accessed 03/06/2020).

[14] ‘Activist Mourned’, Student, 02/02/1989. https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/25635/02_02_1989_OCR.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed 03/06/2020).

[15] ‘Racist Murder in Edinburgh’; ‘Scotland’s Stephen Lawrence Remembered’, The Voice, 01/02/1999.

[16] ‘Racist Murder in Edinburgh’.

[17] ‘Remember Ahmed’.

[18] ‘Racist Murder in Edinburgh’.

[19] Interview with M. McCrum, 19/06/2020.

[20] Interview with R. Arshad, 17/01/2020.

[21] R. Arshad & M. McCrum, ‘Black Women, White Scotland’, Scottish Government Yearbook (1989); M. Jolly, Sisterhood and After: An Oral History of the Women’s Liberation Movement, 1968-Present (Oxford, 2019), p.118.

[22] ‘Focus’, Marxism Today, (August 1982); ‘An Analysis of the Landmark Bradford 12 Trial’ https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/uk.hightide/b-12-trial.pdf (accessed 03/06/2020). Tarlochan Gata-Aura later established WordPower Books (today’s Lighthouse Books, West Nicolson Street, Edinburgh), Scotland’s leading independent radical bookstore, with his partner, Elaine Henry, in 1994. T. Allen, ‘13th WordPower Book Fair Opens’, https://thenoseinvestigates.wordpress.com/2009/10/30/13th-wordpower-book-fair-opens/ (accessed 03/06/2020).

[23] Correspondence with P. de Lima, 15/06/2020.

[24] Interview with G. Younge, 10/06/2020; correspondence with P. de Lima, 15/06/2020.

[25] Arshad & McCrum, ‘Black Women, White Scotland’.

[26] Interview with G. Younge, 10/06/2020; correspondence with P. de Lima, 08/07/2020.

[27] Interview with J. Weir, 07/07/2020; Weir, Murder of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh.

[28] ‘Fighting Racism’, Counter Information, (April/May/June 1989), http://www.thesparrowsnest.org.uk/collections/public_archive/6666.pdf

[29] Interview with M. McCrum, 19/06/2020; interview with J. Weir, 07/07/2020; Weir, Murder of Axmed Abuukar Sheekh, p.7.

[30] ‘Racist Murder in Edinburgh’.

[31] ‘Racist Murder in Edinburgh’.

[32] Interview with M. McCrum, 19/06/2020.

[33] ‘Racist Murder in Edinburgh’.

[34] Interview with G. Younge, 10/06/2020.

[35] ‘Anti-Nazi March’, The Student, 26/11/1992.

[36] Interview with R. Arshad, 17/01/2020; S. Geenan, ‘Stabbing that exposed Scots racism’, Guardian, 08/12/2000; S. Geenan, ‘Scottish judge racist, murder case review finds’, Guardian, 25/10/2001.

[37] A. Anwar, ‘How racism and police brutality shaped my life’, National, 07/06/2020 https://www.thenational.scot/news/18501332.aamer-anwar/

(accessed 08/06/2020).

[38] Professor Rowena Arshad is Chair of Multicultural and Anti-Racist Education at Edinburgh University. Mukami McCrum is the chair of Kenyan Women in Scotland and a board member of Christian Aid. Professor Uma Kothari teaches migration and postcolonial studies at Manchester University. Professor Philomena de Lima researches social justice issues, including racism in rural contexts, at the University of the Highlands and Islands. Gary Younge is an award-winning author, journalist and Professor of Sociology at the University of Manchester.

[39] ‘May Day Celebrations’, Anti-Apartheid News, (June 1990), http://psimg.jstor.org/fsi/img/pdf/t0/10.5555/al.sff.document.aamp2b4300006.pdf Mukami McCrum wanted to work on two fronts – fighting apartheid in South Africa and racism in Scotland. The white-led anti-apartheid movement, however, felt short of resources, and preferred to raise money rather than fight local racism.

[40] ‘Remember Ahmed’.

[41] ‘Anti-Nazi March’, The Student, 26/11/1992; B. Thomas, ‘Nazi Thugs Storm Rally’, The Student, 03/12/1992. Although their public support was limited, white nationalists were also present and the rally was briefly “stormed” by a dozen members of the British National Party holding Union Jacks and white power banners.

[42] P. Gopal, ‘Britain’s Record on Racism is No Less Bloody Than America’s’, Huffington Post, 01/06/2020 https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/george-floyd-death-racism_uk_5ed4ec91c5b62a00d5816f34?ncid=other_huffpostre_pqylmel2bk8&utm_campaign=related_articles (accessed 03/06/2020).

[43] ‘Remember Ahmed’.

[44] C. McDonald, ‘Lawyer: Probe into Sheku Bayoh is first to examine race’, Sunday Post, 24/05/2020 https://www.sundaypost.com/fp/lawyer-probe-into-death-of-sheku-bayoh-is-first-to-examine-issue-of-race/ (accessed 03/06/2020).

[45] Joan Weir and others campaigned for the case to be re-opened in 2012, but by this point Terence Reilly had reportedly died. Interview with J. Weir, 07/07/2020; B. Currie, ‘Call for fresh inquiry into ‘racist’ killing’, Glasgow Herald, 11/02/2012

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/13044453.call-for-fresh-inquiry-into-racist-killing/; B. Currie, ‘Solicitor General confirms racist murder under review’, Glasgow Herald, 18/02/2012

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/13047656.solicitor-general-confirms-racist-murder-under-review/ (accessed 07/07/2012).